UNESCO Heritage

UNESCO heritage

UNESCO World Heritage Sights

Armenian civilization is regarded as one of the five oldest in the world, with Armenians having crafted numerous architectural wonders throughout history and making significant contributions to the development of human civilization. Despite its relatively small size, Armenia is home to seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Additionally, there are Armenian UNESCO World Heritage sites located in present-day Turkey and Iran.

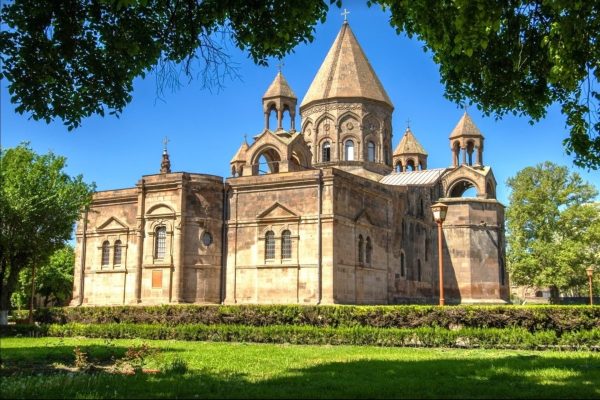

Echmiadzin Cathedral

The Mother Cathedral of Etchmiadzin stands as the spiritual heart of Armenia and the primary

cathedral of the Armenian Apostolic Church, located just half an hour from Yerevan. Within the sacred grounds of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, you'll find the residence of the Catholicos of All Armenians, the Gevorgyan Seminary, the central spiritual hub of the Armenian Apostolic Church, along with the seminary dormitory and a museum complex.

Built in 303, the cathedral was constructed shortly after Christianity was declared the official state religion of Armenia in 301. It holds the distinction of being the world’s oldest continually operating Christian church.

Inside the temple museum, you’ll find some of the most precious Christian relics, including the Lance of Longinus, a fragment from Noah’s Ark, the relics of St. Stephen, a piece of the scepter of Apostle Bartholomew, and many more sacred artifacts.

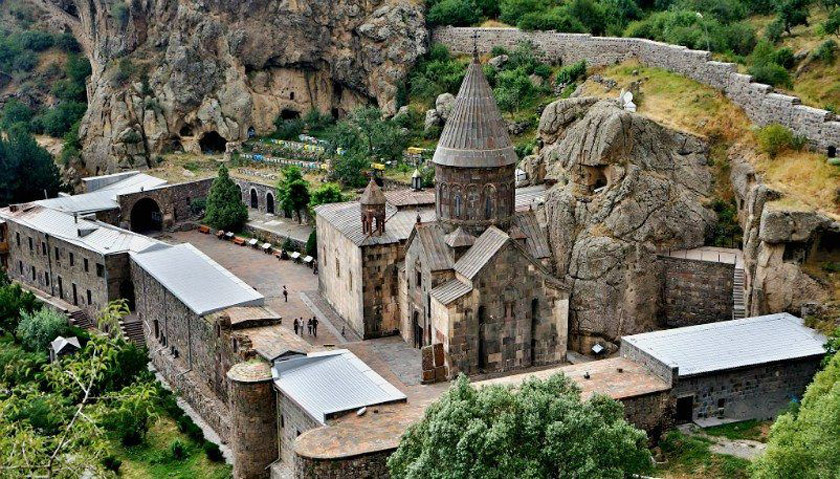

Geghard Monastery

Geghard Monastery is a remarkable site of global importance, rich in intriguing legends and history.

The complex was originally founded by Gregory the Illuminator in the 4th century at the location of a sacred pagan spring inside a cave, which still exists today. This is why the monastery was initially known as Ayrivank, meaning "cave monastery."

The main church of the complex was completed in 1215, and a water supply system was introduced to support the monastery. In the 1240s, the first cave church was carved into the rock, right at the site of the original cave with the sacred spring.

he monastery was later named Geghard, or more specifically, Geghard Monastery, meaning “Monastery of the Spear.” According to historical records, the Spear of Longinus, the weapon that pierced the body of the crucified Jesus, was kept here from 1250 onward. It was believed to have been brought to Armenia by the apostle Thaddeus in the 1st century. As a result, Geghard became a major pilgrimage site for Christians for many centuries. The Spear of Longinus is now housed in the Etchmiadzin Museum.

Today, Geghard is one of the most visited and revered pilgrimage destinations for Christians from all over.

Zvartnots Temple

Armenian architecture is an art form that endures when songs and traditions have faded into silence.

A prime example of this is the iconic Zvartnots Temple, once one of the tallest structures of its time (standing at 45-49 meters), often referred to as the Temple of Heaven Angels or the Temple of

Gregory the Illuminator.

Built in the second half of the 7th century, Zvartnots Cathedral holds the distinction of being the world’s oldest Christian church built in a circular design. As such, it is considered the origin of a new architectural style, making it a significant milestone in the history of architecture. Its cultural and historical importance led to its inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2000.

One fascinating story associated with Zvartnots comes from 652,

when the Byzantine Emperor Constantine was reportedly so struck by the temple’s grandeur that he sought to have a similar structure built in his own empire. He even brought along the temple’s architect, but tragically, the architect fell ill and died before the project could come to fruition.

Church of St. Hripsime

The Church of St. Hripsime is an extraordinary example of early medieval architecture, and its

design inspired the construction of many churches across the Christian world. Founded in 618 by

Catholicos Komitas, it celebrated its 1400th anniversary in 2018 and continues to serve as a place of worship to this day.

St. Hripsime, originally an Armenian Apostolic saint, was later canonized by churches worldwide, gaining recognition as a universal holy figure. The church's rich history is chronicled in the writings of several 5th-century historians.

Regarded as one of the most remarkable achievements of early medieval Armenian architecture, the Church of St. Hripsime may not be the earliest of its kind, but it gave rise to a distinct architectural style known as the "Hripsime type."

In 2000, along with the Etchmiadzin Cathedral and the Church of St. Gayane, the Church of St. Hripsime was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List for its cultural and architectural significance.

Sanahin Monastery

Armenia is home to around 4,000 historical monuments, several of which hold global significance. One such masterpiece is the medieval Sanahin Monastery.

The main structure of the monastery was built in 934 and has withstood the test of time. Other

buildings within the complex were constructed between the 10th and 13th centuries.

Following the establishment of the Tashir-Dzoraget kingdom in the late 10th century, Sanahin

became one of the key spiritual hubs of northern Armenia. Most notably, it was here that one of the world's earliest educational academies was founded.

Today, the Sanahin Monastery is recognized as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site,

highlighting its historical and cultural importance.

Church of St. Gayane

There are seven historical monuments in present-day Armenia that are officially recognized on the

UNESCO World Heritage List. Among them, one of the most visited and celebrated sites,

acknowledged as a treasure of humanity, is the Church of St. Gayane.

Constructed in 630, the Church of St. Gayane stands near the Cathedral of the Holy Mother See of Echmiadzin. The design of this church was groundbreaking for its time, as it introduced the innovative use of sub-dome pillars—an architectural technique that had not been seen before. While the tetraconch layout (a cross-shaped plan with rounded ends) was the traditional design for churches of that era, St. Gayane’s unique construction marks a significant departure from that convention.

This church is not only a prime example of Armenian architectural brilliance but also an important piece of early Christian architecture on a global scale.

Haghpat Monastery

Haghpat Monastery stands as one of the finest examples of Armenian medieval architecture. In the late 9th century, the Bagratuni dynasty of Armenia finally freed the region from Arab domination, leading to the establishment of four distinct Armenian states: the Kingdom of Ani, the most powerful and influential; the Kingdom of Vaspurakan; the Syunik Kingdom; and the Kingdom of Tashir-Dzoraget. Haghpat Monastery emerged as the spiritual center of the Tashir-Dzoraget Kingdom, serving as the seat of the Tashir Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Construction of the monastery's first church began in 976 and was completed in 991. Between the 11th and 15th centuries, Haghpat became renowned for its scriptorium and school, as well as its notable tradition of miniature painting. The monastery is also famous for its wealth of khachkars, intricately carved stone crosses that serve not only as memorials but also commemorate various historical events. Among these, one of the most distinctive is the "Amenaprkich" (All-Savior) khachkar, a rare masterpiece with only about 30 known examples worldwide.

UNESCO heritage

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List

UNESCO established its Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage with the aim of ensuring better protection of important intangible cultural eritages worldwide and the awareness of their significance. We are attaching to your attention UNESCO Armenian Cultural Heritage Background.

Duduk Music

The duduk is a traditional Armenian wind instrument that has been an integral part of Armenian culture for over 3,000 years. Historically known as "tsiranapogh," meaning "apricot pipe," the instrument was first mentioned by the 5th-century Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi. This name highlights the unique material from which the duduk is crafted—apricot wood—which is prized for its ability to produce a resonant, soft sound that closely resembles the human voice rather than traditional instrumental music.

The duduk is not just a musical instrument; it is a symbol of Armenia itself, with its haunting melodies serving as a bridge connecting Ancient Armenia to the modern era. Its evocative sound carries the emotional weight of Armenia's history and cultural journey.

In recognition of its significance and cultural value, UNESCO officially listed the duduk and its music in the World Intangible Cultural Heritage Fund in 2005, acknowledging it as one of Armenia’s oldest and most unique musical instruments.

Khachkar Culture

The khachkar, a stone carved in the shape of a cross, is a quintessential element of Armenian culture. Originating in Armenia in the 4th century, shortly after the country’s official Christianization, the khachkar is a unique symbol that can only be found in Armenia.

The term "khachkar" is derived from two Armenian words: "khach," meaning "cross," and "kar," meaning "stone." Typically, a khachkar is an upright stone monument, with a cross carved into its surface. From its inception, there were specific guidelines and techniques for creating these stones.

The base consists of a horizontal stone block with a hole, into which a vertically placed slab, decorated with inscriptions and patterns, is inserted. Khachkars are commonly made of basalt, which is highly durable, or tuff, which is easier to carve.

The central motif of the khachkar is always the cross, symbolizing the Tree of Life. However, these stones are often adorned with intricate, geometric patterns, particularly in the shape of nodes. These decorative elements typically cover the entire surface of the khachkar, with no defined beginning or end, representing eternity.

Each khachkar is unique, with its own specific symbolism and name, often related to a particular theme or historical event. For example, the “St. Sarkis” khachkar is believed to protect lovers from the “evil eye,” while the “Cross of Genesis” is thought to tame the forces of nature.

Kochari Dance

Kochari is one of the oldest Armenian dances, with roots tracing back to the era of Zoroastrianism. During this period, the ram was revered as a symbol of bravery and strength in the Armenian Highlands. The dance imitates the movements of a ram preparing for battle, allowing the dancers to draw strength and power from the animal’s energy.

Traditionally, Kochari is performed with the dancers' shoulders pressed closely together or even wrapped around each other’s shoulders, forming a united line. Initially, it was a dance exclusively for men, symbolizing a rite of passage, often performed before important events or battles. It was seen as a “Victory Dance.”

Over time, however, as the dance lost its ritual significance, women also began to partake in it.

In December 2017, Kochari was recognized by UNESCO and added to its list of intangible cultural heritage. UNESCO described it as “a dance symbolizing tolerance, preserving historical, cultural, and ethnic memories, and fostering mutual respect among people of all ages.”

Lavash

Lavash is the oldest known Armenian bread, holding a sacred place in Armenian culture and daily life. For Armenians, no meal or even existence can be imagined without it. Lavash transcends food—it is a symbol of tradition and reverence. This unleavened bread, made from wheat flour, salt, and water, is rolled out thinly and baked in a traditional oven. It typically measures about one meter in length, half a meter in width, and is only 2-5 mm thick.

The bread is baked in a special oven called a "tonir." This is a deep, narrow pit lined with clay, where a fire is kindled at the bottom, and the pit is covered with a lid to create the ideal baking environment.

There is a longstanding Armenian belief that bread should never be cut with a knife, but instead broken by hand. To cut bread is seen as a bad omen, as it is thought to bring misfortune or disrupt prosperity.

The tradition of baking lavash has remained virtually unchanged for thousands of years. The recipe, the technique, and the role of women in preparing the bread have all been passed down through generations. Even today, brides continue to carry lavash on their shoulders with reverence, and mothers teach their children to honor this sacred bread.

Sassountsi David

"David of Sassoun" is the widely recognized title of a medieval Armenian epic poem, though its

original name is "Sasna Tsrer," which translates to "The Brave Sassounians".

"Sasna Tsrer" narrates the tale of courageous men from the mountainous region of Sassoun (present-day Turkey) who rose up against oppressive Arab tax collectors. The epic centers on a fiery, strong

young man named David, who, as he matures, channels his formidable strength into defending his people from foreign invaders.

Since "Sasna Tsrer" is a folk epic that was passed down orally over generations, its exact date of

origin remains uncertain. However, scholars generally place its creation between the 8th and 10th centuries.

David of Sassoun is a beloved figure in Armenian culture. One of his most iconic representations in visual art is the bronze statue sculpted by Yervand Kochar in 1959, which stands proudly in Yerevan’s Station Square.

On December 5, 2012, UNESCO officially added the Armenian national epic “David of Sassoun” to the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Armenian Alphabet and Calligraphy

Few nations hold their written language in as high regard as the Armenians. For them, the alphabet is not just a means of communication, but also an artistic expression. Armenian letters are often seen as decorative elements, woven into carpets, crafted into brooches, and incorporated into photo frames. In fact, Armenian calligraphy features distinct styles, with letters taking the form of birds, flowers, plants, people, and even animals.

What sets the Armenian language apart is that it is one of the few cultures where the creator of the alphabet is known by name, and his legacy is well-documented. The inventor of the Armenian alphabet, Mesrop Mashtots, created it in 405, and his tomb can still be visited in Armenia.

The Armenian alphabet has remained unchanged for over 1600 years, making it a remarkable example of linguistic continuity.

It also has its own Braille system, which was first implemented in Armenia in 1921 by the renowned composer N. Tigranyan in one of the schools he founded in Gyumri.

For centuries, the Armenian alphabet has played a central role in shaping both Armenian identity and national survival. This profound connection with their written language explains why Armenians hold it in such sacred esteem. Today, there are two notable monuments to the Armenian alphabet in Armenia: one is located in the village of Oshakan, at the church where Mashtots is buried, and the other stands near the slopes of Mount Aragats, the highest peak in Armenia.

Pilgrimage to St. Thaddeus tomb (monastery)

According to Christian tradition, the Apostles Thaddeus and Bartholomew traveled to Armenia in AD 45 to spread the teachings of Christ. During their mission, many people converted to Christianity, and numerous secret Christian communities were established throughout the region.

Thaddeus, one of Christ's twelve apostles, was martyred in Armenia under King Sanatruk. He is honored as an apostle of the Armenian Church. The first church dedicated to him was built on the site of his tomb in AD 66, though some sources suggest its foundation occurred in AD 239 by St. Gregory the Illuminator.

Another tradition holds that Thaddeus himself established a monastery at this location for his followers, who later buried him there upon his death. The precise date of the monastery’s construction remains uncertain.

The tomb of St. Thaddeus is located in what is now modern-day Iran, making him the only one of Christ’s twelve apostles whose burial site is known.

Each year, the St. Thaddeus Monastery hosts an annual pilgrimage and ceremony from July 14 to 16, drawing pilgrims from all over to honor the apostle’s memory.